Logging Companies Tout Big Plans for Big Trees - Redwood Forests Will be Managed with Concern for Ecosystem

Logging companies tout big plans for big trees:

Redwood forests will be managed

Glen Martin, Chronicle Environment Writer The San Francisco Chronicle

March 22, 2004

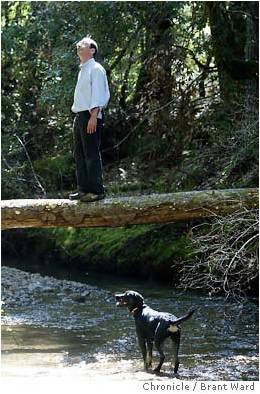

Forester Fred Euphrat, joined by his dog Holiday, examines redwoods along Mill Creek on his family's land near Healdsburg. He said logging methods there consider environmental impacts.

Chronicle photo by Brant Ward.

For the most part, California's primeval coastal redwood forests are long gone, transformed into Victorian mansions and wainscoting. Only about 5 percent of the virgin stands remain. About 2 million acres of second- and third-growth redwood forest still exist, but about one-third of that total consists of residential areas in Santa Cruz and Sonoma counties. The remaining 1.3 million acres is commercial or "working" forestland -- most of it in the northern coastal counties, and much of it too degraded and eroded to support the fish and wildlife species endemic to the primordial groves.

Although redwood trees are not considered to be endangered, scientists have warned for years that ancient forest ecologies are on the brink of extinction. A second-growth stand of even-aged redwoods, they observe, is basically a tree farm, sharing little in common with the twilight world of the old-growth forests, where trees are so large that only 30 grow to the acre, supporting rare deep-forest species such as coho salmon, marbled murrelets, northern spotted owls and fishers.

But now, some scientists and professional foresters are sensing a turn for the better. Bad as things look for the redwoods, they say, the nadir may have been reached.

"On our properties, we're planning on a landscape scale, focusing on identifying and preserving our old-growth stands, and improving stream and upslope habitat," said Sandy Dean, an executive for Mendocino Redwood Company, a firm that owns more than 230,000 acres of working redwood forest and emphasizes a "sustainable" approach to timber harvests.

Dean spoke at a UC Berkeley-sponsored symposium last week in Sonoma County on the state of the redwood forests.

The meeting included some grim discussions of such familiar redwood threats as global warming, urban development and infectious disease. At the same time, forest researchers said they are seeing glimmers of classic old- growth characteristics emerging in carefully managed second-growth redwood stands.

Hopes are centered on an increasingly popular management philosophy for the second-growth working forests that favors streambed rehabilitation, conservation easements, slope stabilization and conservative harvesting plans.

Forest specialists who once concentrated on finding more efficient ways to harvest the big trees are now focusing on re-creating the ancient redwood ecologies that existed before Europeans settled California.

"If this symposium had been held 20 years ago, it would have been about 101 ways to cut down trees," said Greg Giusti, a forest and wildlands ecology adviser with the cooperative extension program at UC Davis.

"Instead, it focused on forest science, about restoring the essentials of the ancient redwood system within the working landscape," said Giusti. "I find that grounds for some optimism."

Giusti said many commercial foresters are trying to manage their redwood properties in a way designed to bring back old-growth characteristics.

"In a nutshell, certain types of silvicultural practices -- such as commercial thinning and prescription fire -- can accelerate aspects of an old-growth forest," Giusti said. "After about 90 years, you start to get that certain feeling you only get in an old-growth stand. The trees are getting widely spaced, and beginning to look a particular way. The humidity is high, the atmosphere hushed. You find yourself talking in a whisper."

Still, said Giusti, "even with enlightened management, you have to realize some ecological components will remain decades away. You're not going to see the big, flattened branches and the deep burn cavities in the trunks --

and the niches they provide for various species -- for a very long time."

About sixty papers were presented at the symposium covering nuts-and- bolts management issues, tree genetics and amphibian and plant species uniquely associated with ancient stands.

But a great many papers seemed to reflect the swelling interest in active redwood restoration. A significant number were concerned with controlling erosion, thinning groves as a means of achieving old-growth configurations, improvement of coho habitat and the role of fire in maintaining primeval forest characteristics.

Still, no hard evidence was presented suggesting redwoods are, so to speak, out of the woods. Indeed, Giusti spoke for the consensus: While the game plan seems increasingly clear, the game will run very long indeed.

"For 150 years, redwood forests were aggressively managed to take out (timber)," Dean said. "There's nothing we can do about that, and we have to live with the consequences. But we can also work to improve the forest now."

At Willow Creek Ranch, a 5,000-acre Mendocino Redwood holding on the lower Russian River, company staffers demonstrated how the sustainability philosophy translates on the ground.

Mendocino Redwood forester Colby Forrester pointed to a lowland grove of large second-growth redwoods whose muddy terrain once drew four-wheel-drive vehicle enthusiasts.

"This was a favorite site of mud boggers," he said. "The sedimentation into Willow Creek was terrible. So we fenced off the grove, and most of Willow Creek as well. Then we put down a lot of slash (woody debris) to stabilize the soil. It's had a really beneficial effect."

The company also conducted a selective cut on slopes near the mud-bogger grove. But it was a light harvest, making it difficult to tell that any trees recently had been cut.

"What we're trying to do is break up the even-aged stands, to convert them to a mixed-age configuration that more truly resembles an older forest," said John Anderson, another Mendocino Redwood forester.

Environmentalists remain somewhat chary of sustainable forestry practices, arguing that they are sometimes New Age euphemisms used to describe regular old commercial logging methods that have been changed minimally. But some are heartened by the talk of using carefully managed working forests as biologically functional corridors connecting old-growth reserves -- as long as the walk matches the talk.

"The working forest is the essential linkage, the matrix," said Kate Anderton, the executive director of the Save The Redwoods League. "It (the working forest) is critical to what happens in the ancient forest reserves. But to restore the ancient system, we have to determine if the preserves are large enough and if they're linked appropriately."

Ultimately, said many participants at the UC Berkeley symposium, there has to be an accommodation among ecological, economic and social needs if any restoration plan for the second-growth forests is to succeed.

Art Harwood, a Mendocino County mill owner and a champion of sustainable forestry, said free trade has made even prime redwood just another commodity in the global marketplace.

"Redwood now competes directly with exotic hardwoods from Brazil," Harwood said. "Adding to our burden (in California) are stringent regulations and high labor costs, things that aren't an issue in South America."

Harwood said redwood producers must survive by constantly monitoring global timber developments, exploiting niche markets and viewing the sustainable forestry movement as an opportunity rather than a problem. Seals of approval from groups such as the Forestry Stewardship Council, which certifies lumber from sustainable sources, can add value to a wood product, Harwood observed.

"We need the support of environmental groups," Harwood said. "It'd be great to have them do your marketing for you, especially for redwood. And (if the lumber was produced in sustainable fashion) they'd do that."